The Satsuma Biwa

A Radio 3 interview with Ueda Junko

transcribed, translated and summarized by E. Steenput

Ueda Junko learned to play the Biwa and to sing Japanese epic songs from the famous composer and performer Suruta Kinshi. Suruta sensei did not only compose herself, she also inspired other composers such as Takemitsu Toru to write for the Biwa. Mrs Ueda has been living in the Netherlands for several years, and the interview was conducted in Dutch.

The Biwa is a wooden, pear-shaped lute with four or five strings made from silk, a crooked neck, and played with a large triangular plectrum. This instrument has high frets and the strings are loose, which allows variation of the pitch by depressing the strings directly behind the fret. There are no fixed tunings. The player adjusts tuning and left-hand fingering to obtain the desired pitches.

There are various forms of Biwa in Japan, such as the moso biwa and the gaku biwa. These different styles were used for different kinds of music aimed at different audiences. The gaku biwa is the oldest type and dates from the 7th century when it was used for Gagaku court music, where it supports the rhythm of a piece. The gaku biwa of the court music was a large instrument laid with the neck horizontally and played with a small plectrum. The moso biwa was a smaller biwa with a larger plectrum used as solo instrument by blind monks, and it was this type that evolved into the Satsuma biwa, Chikuzen biwa, and other styles of biwa. Blind priests recited epics and ballads of a religious or secular nature. These biwa styles evolved in parallel, not sequentially. The gaku biwa was popular in the West, the moso biwa in the South of Japan.

The large plectrum is triangular, with a largest side of about 27 or 30 cm. Special sound effects can be obtained by striking the wooden body of the biwa with the plectrum. Very different sounds can be produced with this plectrum, such as by scraping along the strings. However these are modern techniques, not traditional ones, says Mrs Ueda.

Mrs Ueda plays the Tsuruta style biwa, invented by her teacher (who died 2.5 years ago (at the time of the interview)). About 100 years ago the biwa tradition was very popular, there were more than 30 biwa builders in Tokyo alone, and biwa songs could be heard on every street. However, after the war there remained only one biwa builder active in the whole of Japan (and the world) and the tradition was disappearing. Biwa faced extinction, because most of the texts accompanied by biwa were related to samurai spirit.

Tsuruta Kinshi wanted to recover, preserve, and redevelop the tradition.

Mrs Tsuruta used to say tradition is not something locked up in a museum, tradition is a challenge. She could play the traditional pieces very well, but was convinced that tradition must grow to remain alive. And so she changed the tradition, by changing, improving the instrument. She reduced the biwa's thickness and enlarged the plectrum, and introduced many new techniques for playing the biwa. Tsuruta experimented. For example, she tried to use the broader part of the plectrum, whereas the traditional Satsuma biwa uses only the edge.

The music of Takemitsu not only helped the old traditions to survive, but also simulated public appreciation of traditional Japanese music. Takemitsu said "Music is either sound or silence." This "silence" called "ma" is as important as a sound in Japanese music. "Ma" is the effective silence for next sounds, and emphasizes each phrase. It is similar to "rest" in European music, but each duration of "ma" is different.

Tsuruta once said to Takemitsu, "I want to learn the Western notation." Takemitsu replied, "That's the last thing I want you to do. I will learn traditional Biwa notation, and you do not have to know the Western notation." Takemitsu also said, "Today, traditional sense of sound is getting extinct, because of the Western tuning and notation systems." According to him, Tsuruta had a "pure" sense of Japanese sound, and he wanted to keep it.

Biwa music sings about heroes and civil wars of the samurai period in classical Japanese language. Biwa accompanies the vocal part of narratives, and uses a rich variety of sounds so as to express the scenes. Instrumentally, the music can be very interesting, but real appreciation requires an understanding and sympathy with the lyrics.

Heikyoku (Episodes from Heike Monogatari) were chanted to the accompaniment of the biwa. This work is attributed to Yukinaga, an official and courtier of the cloistered Emperor Go-Toba (r 1183-98) who later became a Tendai monk at Mt Hiei. Yukinaga worked with a blind monk, Shobutsu, and incorporated elements of court music, Buddhist Chant and Moso Biwa. The heikyoku came to overshadow any other military tales told on the Biwa. The heikyoku contains 200 pieces, of which 176 are ordinary pieces (hira-mono), 19 are secret (hikyoku) and 5 are very secret material (hiji). Another way to classify the work is; fushi-mono (lyrical pieces), hiroi-mono (narrative battle pieces), yomi-mono (recitation pieces).

Mrs Ueda concluded the interview by singing "DannoUra", an episode of the Heike Monogatari. DannoUra is an inlet or inner sea in South Japan, where the struggle between the Heike (Taira) and the Genji (Minamoto) clans reached its climax. This is a battle on the sea, and there is some heavy action in the middle, but in the end the Heike are annihilated, and all that remains are empty boats with only women and children. The song ends when a noble lady and the Emperor, who was 7 or 8 years old at the time, jump in the water to drown. A very tragic story.

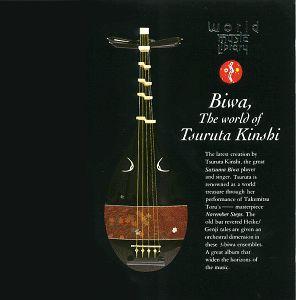

Works performed by Tsuruta Kinshi

can be found on the CD Biwa:

The World Of Tsuruta Kinshi.

(follow the link to hear some samples)