Kenjutsu, the Art of Japanese Swordsmanship

by Charles Daniel

Unique Publications, 1991

123 pages, $12.95

Opinion: NOT recommended

A short version of this review appeared in the Journal of Japanese Sword Arts, June 1998.

From the cover:

"Now, for the first time in the West, Japanese swordsmanship expert Charles Daniel brings you the definite text on the art of the Japanese blade, and the legendary men who carried them" (sic).

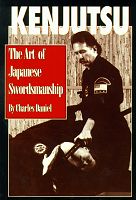

The cover of the book shows someone (not the author. According to John Lindsey, it is Chadwick Minge, wearing the Genbukan patch) executing some jujutsu technique using the tsuka of a sheated sword.

What it's about:

The author, Charles Daniel, doesn't once mention the style(s) he studied, nor his teachers and credentials. There is no clue as to what the book is supposed to offer, or how it is meant to be used. I know from "The grandmaster's book of ninja training", a collection of interviews with Masaaki Hatsumi, that the author fenced the foil and is one of the Bujinkan elite. He also wrote "Taijutsu: Ninja Art of Unarmed Combat", and "Traditional ninja weapons", so presumably this book is about the real ninja swordsmanship.

The book starts with a series of short texts on the Japanese sword, the usual discussion on how kendo doesn't teach one to cut but only to tap, the relation between swordsmanship and other martial arts, and half-page biographies of Tsukahara Bokuden, Yagyu Muneyoshi, Miyamoto Musashi and Ito Ittosai. The material presented in these short essays is not very accurate and even contradictory. For example: "On the battlefield, a large katana called a Daito, or the slightly smaller Tachi was used. These swords could be as long as five feet and were used to cut down horses (and their riders) as well as a few enemy soldiers with one cut. Of course, such swords were not worn in the everyday world, and after the beginning of the Edo period, c. 1600, the shorter katana proper came into fashion."

It is then explained that the different kenjutsu ryu are actually only different in their kata, the basic movements (suburei (sic)) are pretty much the same. Supposedly the book deals with those basic techniques "common to all ryu". Indeed, the bulk of the book consists of examples of basic (and not so basic) partner exercises that one could practice, presumably to complement one's unarmed art.

Techniques:

The technical part consists of sword grip, stances, distance and timing, mutual slaying, simple attacks, beat attacks, simple counters, parrying techniques, reinforced blocks, wrist cuts, nito and katsijinken (sic).

Fourteen stances are given, the usual and some unusual. One of the kamae (honguaku) is attributed to Ono ha Itto ryu, yoko to the Tenshin ryu (?), gyaku yoko to "Yagyu swordsmen" and another (nameless) to "Katori and Kashima styles". That's as close to identifying his style as the author gets.

The techniques are presented in photographs with short explanations. Posture and footwork are almost never mentioned. This, among other hints, suggests the book is aimed at a specific audience, presumably the reader must be familiar with standard ninja taijutsu. As a reference for basic ninja sword movements, this book probably serves a purpose. There aren't that many books on basic kumitachi exercices, but even then this one is very sloppy: the photos show the author with other people in black ninja suits wearing tabi and wielding bokuto against a dark background of trees under poor lighting. Some of the photographs are obviously out of order.

As to the techniques themselves, it is hard to judge technique based on pictures, but some of the stuff seems rather questionable. The footwork looks strange but is never explained. Quite a few times the distance suggests uchitachi attempts a tsuka strike to the head rather than a cut. If an opponent will ever let you come that close, then those techniques will probably be effective...

The text in the nito section repeatedly refers to Musashi, but the techniques are certainly not from Hyoho Niten Ichi ryu. By the way, Katsijinken (sic) consists of using one's sword to disarm/throw the opponent without killing him, and muneuchi (strikes with the mune).

Not a single 'kenjutsu' kata is given in 'Kenjutsu', but the latter part of the book extensively discusses eight jujutsu katas from Takagi Yoshin ryu, some involving sword disarms or use of the tsuka or saya. While illustrating the use of sword parts in jujutsu techniques might be appropriate, I don't understand why this section is more elaborate than any previous part of the book. A list of body targets is given for Koto ryu koppo jutsu, also for reasons unexplained. This section includes the following bit of kenjutsu wisdom: "Weak points can occur within someones balance, stance, mental outlook... the confusion as to what is an actual weak point as opposed to a simple sensitive spot on someone's body is one very important reason most martial artists spend their entire life training and still reach only a rather insipid level of skill."

The jujutsu kata are demonstrated with metal swords. One of the techniques consist of more or less turning your back to the attacker as he cuts down, and to strike the underside of his wrists with the saya. This kata ends with the attacker floored and his (replica, I hope) sword sticking in the ground!

Ittosai's Instructions

Just before 6 pages at the end with the single word "notes" on them, there's an epilogue, called "Ittosai's Instructions". These five pages are the most interesting part of this book, and almost make it worth reading. The text is supposedly the translation of the first part of an unnamed text written by Ito Ittosai.

Unfortunately the book lacks a bibliograhy or source reference list. The author only mentions that: "Fortunately, the scrolls left by Ittosai are still in existence and can be obtained by those who have the connections and luck...What follows are the first parts of the instructions left by Ittosai. Here, he writes about some of the central points of swordsmanship..."

According to prof. Friday, the text seems to be inspired on Itto Ryu hyoho junikajo, a document dated an auspicious day of the third month of Tenmei 8 (1788), and signed by Ono Jiro Uemon Tadayoshi (NOT Ittosai himself). The original document lists the names of the twelve items Daniel discusses, but does not include the explanations he offers. Prof. Friday couldn't find any such explanation of these terms in anyof the Itto Ryu literature. Wherever these explanations come from, they aren't from classical Itto Ryu documents, much less from from Ittosai himself. The terms themselves, as Daniel reports them, are, btw, rather badly corrupted, suggesting that he either had the world's worst proofreader or that he doesn't have even a passing familiarity with Japanese phonetics.

Prof. Friday offers the following translation of the whole document

(source: Nihon: budo taikei, vol.2, p. 135):

( Disclaimer: this is a very rough and very literal translation,

not a polished piece of scholarship )

Twelve Tenets of the Itto Ryu Martial Tradition

- Futatsu no metsuke no koto (Two points of eye contact)

- Kiriotoshi no koto (To cut down)

- Enkin no koto (On distance and closeness)

- Ojujoge no koto (Horizontal, vertical, up, down)

- Irotsuke no koto (Applying color)

- Mokushin no koto (On the mind's eye)

- Kogishin no koto (On doubt/hesitation)

- Matsukaze (or shofu) no koto (On the wind in the pines)

- Chigyo no koto (On the form of the earth)

- Muta shintsu no koto (On the heart transmitting the self)

- Ma no koto (On interval)

- Zanshin no koto (On the remaining mind)

From a young age you have practiced the Itto Ryu for many years. Your devotion has been unslacking and profound. Together [these principles] are all, leaving out nothing. Moreover the workings of victory are within these, thus this one scroll is put forward as the first written document of our style. Polish these and the actuality of certain victory must become realized. Wherefore this list.

Ono Jiro Uemon Tadaaki

Ono Jiro Uemon Tadatsune

Ono Jiro Uemon Tadao

Ono Jiro Uemon Tadakazu

Ono Jiro Uemon Tadakata

an auspicious day of the third month of Tenmei 8 (1788)

Ono Jiro Uemon Tadayoshi [seal]

[To:?] Lord Tsugaru Tosa-no-kami

(end quote)

I found the following quote here: "Kukishinden Ryu is related to Itto Ryu Kenjutsu. There are writings by the famous swordsman Itto Ittosai in the Kukishinden Ryu densho signed and dated March 1st, Tensho (1573)." Maybe this refers to these explanations. Still, it's extraordinarily unlikely that Ittosai was the author of this document. To begin with, bugei-sha of Ittosai's era didn't write explanatory documents of the sort, although the list-of-techniques-and-concepts sort of document was reasonably common. More importantly, it's VERY unlikely that a branch school would have ended up in possesion of a document far more detailed (and thus revealing--and thus important) than the ones possessed by the main lines.

Somehow I don't think Charles Daniel wrote those explanations. For one thing, they are better written than the rest of the book. A small extract :

Ittosai's Instructions

Sometime during his fiftieth year, Itto Ittosai, creator of the famed Itto ryu decided that the time had come for him to devote the rest of his life to the service of Buddha. However, before leaving the world of normal men, Itto was faced with the task of making sure that his ryu would be passed down to the next generation. Taking his two top students to a quiet field, Itto had them fight a duel to the death to decide who would be the next headmaster of the Itto ryu. The winner of the duel received Itto's sword as well as a scroll containing the secrets of Itto's style. The two students were named Zenki and Ono. During the duel, Zenki was killed and later, Ono became a tutor of the Tokugawa shoguns. Unlike many of the sword schools in Japan that trace their origins to some divine revelation, the Itto ryu was a system that evolved directly from the experiences of its founder. Thus, it is one of the most practical of all of the old schools of Japanese swordsmanship.

For anyone interested in the older schools of Japanese fencing, the Itto ryu is both interesting and, to a certain extent, inescapable. Of course, one method of finding out a little about this school would be to visit it in Japan, but that would present some surprising drawbacks. First of all, modern kendo has made inroads into many of the old schools of fencing, and thus caused some modifications in some of the techniques. Also, the old techniques that still do exist are closely guarded and not often shown to the usual visitor. Fortunately, the scrolls left by Ittosai are still in existence and can be obtained by those who have the connections and luck.

What follows are the first parts of the instructions left by Ittosai. Here, he writes about some of the central points of swordsmanship, but the same ideas can be applied to any form of martial art. Of course, if one has some experience at sword technique, then understanding what is written here is somewhat easier.

#1 Fatsumomiska No Koto To see depth and distance, a person needs two eyes. Whenever one looks at a person, it is not enough to just see the person's surface. One must check the entire person. The walk, the hands and the balance of the large and small points. Special points can indicate other body development. That is, what is the "unusual point" connected to (i.e., conditioned hands will reveal one type of training, while large forearms will reveal another)? In the checking technique of the Itto ryu the following points can be used: If your opponent takes seigan no kamae (middle sword posture) or gedan no kamae (lower sword posture), then check his grip, foot position and then the entire body. Mistakes in any of these positions can tell one much about the opponent's abilities and experience. If the opponent assumes jodan no kamae (upper sword posture), then check the sword edge (one indication of distance), the grip of his right hand, and the position of his elbows and then his foot and body position. If the opponent takes waki no kamae (holding the sword back behind the body), then check the grip of his front hand, his footwork and his shoulder.

The point of all this is that you must be able to judge the opponent's actions based on the way he is standing (his posture). If the opponent moves to the right, check his left side; if he moves to the left, then check his right side. Always check in the opposite direction than the one in which the opponent is moving. If one cannot read an opponent's mind through his motion, then check the edge of his sword. If one still cannot read him then one must use his own sword point because the point of one's sword can scare the opponent and thus make him reveal his intentions. The mind is the same as the true body. Even if one has a strong body but his mind is weak (because he is scared or unsure) then he is weak. If one has a weak body but a strong mind, he is strong. One must train so he can check his own mind so that there is no weak point there (such weak points as being scared, excited, unsure or wanting to win). The object of training is to rid one's self of such weak points. However, be careful not to have an "I am strong" mind. One needs to practice naturally. One can check an opponent through his friends, where he lives, etc. One has to keep the body and mind free and flexible. Then from one action, one can check the opponent's next action. One can find the big points through the small points.

#2 Giri Otoshi This technique is the beginning and the end. It is easy to start but difficult to master. When the opponent cuts, then at that timing, enter and do a slide cut. This action will deflect the opponent's sword while placing one in a win position. This action is done with Aiuchi style (mutual killing style) but because of the timing, one wins. Thus with proper timing, one steps straight in and cuts straight down. To do this, one must have mushin (no mind) because no power is used. This works because one's mind is already in a winning position. That is, one's own mind balance is best while the opponents' mind balance is totally broken. To create a winning position like this, one must be able to cut without thinking. Thus, as the opponent cuts, one's own mind is patient in that one does not want to cut the opponent. That is, there is no desire to win. If one is worried or wants to win, then the mind is fixed, and he will not be able to move freely. With mushin, it is easy to check the opponent. For example, if a cat is chasing a mouse too closely, sometimes the mouse will turn and attack, and the cat will have a difficult time in spite of the mouse's small size. However, a good cat will keep a "play" mind and catch the mouse very easily. This type of mind leads to a happy and lucky lifestyle. If one masters Giri Otoshi, then a nice, dignified style will be born. This technique is like a seed dropped onto the ground that will grow and develop into countless techniques.

#3 Inken No Koto In real fighting, the opponent wants to get close enough to win. This is the case for both fighters. Even if the distance is equal, but one side can attack with ease while the other cannot, the true distance is not equal. This is the situation one must study and learn to create. The most important point is to keep the body straight and use footwork to adjust one's distance. One should learn how to make the opponent feel like he is always far away, and thus cannot attack. If the true distance is close for both people, then change position to gain the advantage.

One must keep flexible in the approach to be able to do this. If the true distance is close then it is also possible to use a mind attack. This is done to create distance in the opponent so that even though the physical distance is the same, the mind distance is not. That is, the mind relationship is changed. The decision of life or death balances on very small points. One can use devices (i.e., tricks or other techniques) to break the opponent's balance (mental balance). If one thinks too much or is too scared or too concerned with winning, then he will not be able to find correct technique.

#4 Yoko Tati Joge Koto If your opponent cuts at your body (do giri) then go straight in or straight out. If he cuts downward at your head (shomen ucht), cut straight upward. Use the opposite direction technique for an easy victory. This is the basic idea, but techniques are not fixed. One can break the opponent's balance by using his power against him and this brings an easy win. It is important not to let the opponent control your mind or body, so keep your own rhythm and pace. The point is to make a scale like a ball and only as one starts actions. That is, cut with the sword directly from where it is. If it is high, cut down, and if low, cut up. Don't move your sword around needlessly. In the Itto ryu, a cut from the side (do giri) is katsujinken (life giving), while a downward cut (shomen ucht) is a killing technique. One must cut one's own ego before he can use this technique. One should have a relaxed mind and keep practicing. One's own life and death depend on flexible self-con!rol.

#5 Eroski No Koto If something is in a shadow, then one cannot see what it truly is. That is, the truth is hidden. Often, one's opponent's mind is like this. If one can find the opponent's mind and take it (control it), then victory will be easy. Before one can do this, he must be able to find the opponent's true mind and not be taken in by outside (surface) appearances. One can combine the mind with the sword point, and with these together, break the opponent's balance and win. One's own state of mind must dictate the opponent's state of mind (i.e., make one's own pace). Often, surface appearances can cause confusion, so one must look past these to see the opponent's true mind. It is important to remember that sometimes highly skilled opponents cannot be controlled.

#6 Migokuro No Koto The mind gathers and can be checked through the eyes. When the mind moves, it will start an eye action. Thus, reactions can be seen in the movements of the eyes. This idea can be used in fighting. For example, distractions can be used to move someone's mind. This point should be studied. Here the starting point is the mind and then, a little later, the eye moves. If one will check the eyes along with the opponent's actions, he can see his opponent's true mind. This check should be done in one action, then one can do the techniques without thinking. Look to see where the opponent's mind is. Is it in his hands or his feet or his eye, etc.? If his mind is in his hands, maybe he is afraid. Sometimes his mind will gather in his feet. If one learns how to se where the opponent's mind is, then after this training he can fight in the dark by feeling. If one's own eye is strong (can see the opponent's mind, etc.), then through just one action (of the opponent) one can read everything about him. This is why an old teacher can defeat a young and very strong student; the teacher's eye is stronger. This type of strong eye can be used to contact God.

#7 Kogishin No Koto A fox can run very fast to escape. However, if a dog attacks him and the fox thinks too much about how to escape, he will not escape. Don't use too much thinking. Too much thinking can cause doubt, and this is a problem. If one's own mind is confused like this, then he will not be able to see the opponent's mind and cannot use the technique. If one has doubt in the technique, then the technique will be useless. One gets rid of this by practice and experience. When teaching, one must be careful with the voice because the student will believe.

#8 Shofu No Koto A pine tree has no voice. The wind by itself also has no voice. Together, they have a sound. As the wind blows fast or slow through the pines, it makes different sounds. Wind from the south has a different sound than a wind from the north, and these are different from the sound of the winds in the mountains or by the seashore. It is the same against an opponent. If he changes his style, then adapt. To always have the same style is not good. If one's opponent has a strong style, use a stronger style. If the opponent bas a weak style, then use an even weaker style. This is one type of approach. Another approach is to use weakness when the opponent is strong and use strength when the opponent is weak. These two approaches are very important. If one's opponent is too strong, then confuse his mind with timing, tricks, etc. It is most important that one know his own points (strong and weak) or he will have problems. With the wind and the pine trees, if one is missing then there is no sound. If one's opponent has a fighting mind while one does not, then there will be no trouble (dealing with the situation).

#9 Chika No Koto There are many ground conditions one must be aware of. Sometimes one will meet the opponent on flat ground and sometimes on hilly ground and sometimes on rocky or muddy ground. In addition to these conditions, there are the conditions that one finds in a house or castle. One must learn to always make the best of the situation. If one's actions fit the ground they are on, then the entire technique will be much easier. In all situations, one should keep the body straight and let the feet and legs adapt to the ground. If one is on slippery ground (i.e., ice or wet ground), then one should use a narrow step (small steps). If one finds obstacles on the ground, such as stones, then use a sliding step because using a high step to step over things can cause one to lose balance. If possible, have sunlight to one's back or right. If one faces many attackers, then put one's back to a wall or other cover.

#10 Mutashinsu No Koto This is divided into three steps: (1) Study one thing (the Itto ryu) well. Once one has done this, he can look at other martial arts and adapt them so they are useful to himself. Thus, one can look at other activities through he art. Look through Itto ryu eye. It should be remembered that different activities have different key points that should be checked. (2) If one can't find the opponent's mind, he should not attack because one cannot win like this. One must feel the opponent's mind. This is the basis of the Itto ryu. (3) If one's practice has reached a point where he almost completely understands the Itto ryu, then the opponent will not be able to read his mind. Thus, the opponent is always confused and cannot attack. This makes the opponent weak and afraid and breaks him. As one's practice increases (the amount of time practiced) then he will realize and easy, natural understanding. The personality will grow and he will naturally fit into whatever situation he is in. The mind will not be influenced by the outside world and will always be quiet (inside). This is one high target for the mind practice.

#11 Mai No Koto One starts hitting or thrusting with the posture (stance). One should finish techniques without using much power. The best distance is not too close or too far. It is a "best fit distance." This is one type of mai (distance). One must always use this distance for real fighting. This fit is different for each person. In the Itto ryu, the distance between one's own feet when standing in a stance is about 90 cm. The distance between people (between oneself and the opponent) is about six feet. At a distance of 150 cm between each person, the fight is won or lost if one has the best principle. Winning starts when one has the best distance and the opponent does not. A highly skilled technician always makes the best distance while a low-skilled person cannot. Sword techniques, such as hitting the opponent's sword, etc., are all meant to create this best distance so one can go inside the opponent's guard and attack. When one walks on the street, he should check his distance from other people and create the best distance as a way of practice. When one visits a house, he should mind the distance between him and the host. Mind distance is also important. In a fighting situation, if one's own mind is sharp, then he may "draw out" the opponent's attack. One should not think "want life" thoughts when faced with a real fight. One should take the attitude of Shin No Shin Ken, which means one will not stop even if cut. If one has proper mind distance but technique is not there, he cannot win. One must have both technique and mind distance.

#12 Zanshin No Koto (1) One should only use 88 percent of the mind and body power when doing a technique. If one uses full power, then the next technique is lost. For example, one never cooks 100 percent of the rice because then there is nothing left for the next year if the crops are bad. One should save 12 percent, but at the same time give 88 percent fully and at one time. (2) Mind in technique: If one uses 100 percent of the mind in a technique, then the mind becomes fixed. Mind and body should be used completely together only in the very best situations (for example, when the opponent's mind and body balance are totally broken). However, remember that if one does not put enough mind into a technique then it will be easy to counter. Study this balance. (3) If one does use 100 percent mind and body in a technique, then he should use another principle so as to always have another technique beyond the last. Zanshin is a last caution.

The explanations are at least interesting. It would be nice to know who actually made them up.

Review by Eli Steenput, April 1998